(Dreamstime/Olgers1)

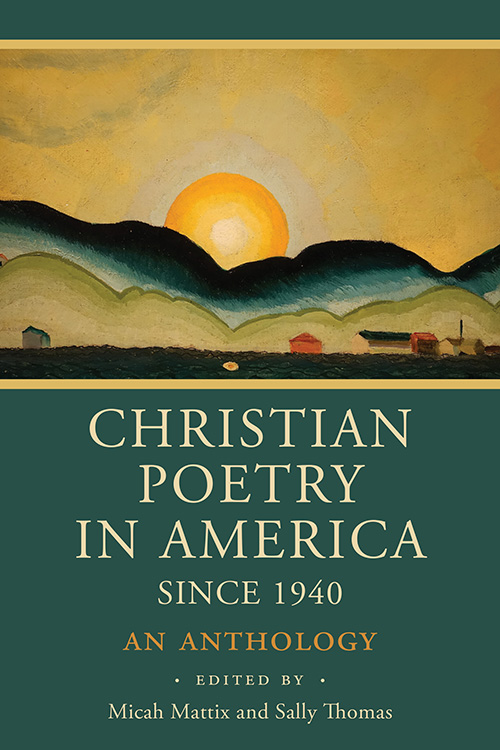

Christian Poetry in America Since 1940: An Anthology, edited by Micah Mattix and Sally Thomas, calls to mind the old quote attributed to Mark Twain, "Reports of my death are greatly exaggerated." As the excellent biographical and critical notes for each of the 35 poets make clear, good Christian poetry can no longer be said to operate in a literary ghetto, if it ever did.

Among the poets, all of whom have been born since 1940, are a U.S. poet laureate, several state poet laureates, a chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and editors and founding editors of major literary journals, fellowships, prizes and awards too numerous to count.

Mattix contributes an erudite introduction exploring the question of what makes Christian poetry in the historical context of Christian literary theory. That, combined with the editors' author discussions, make this anthology an excellent book for classroom use where the requirement for Christian poetry to point mimetically to the transcendent can be fully understood and debated.

But the poems themselves, so many well-crafted and precise, penetrating poems, more than 125 of them, make this book perfect for any and all questing spirits.

The poets' church participation runs the gamut, as does the certitude of their belief. Denominations of choice range from Baptist to Catholic, Orthodox, Presbyterian, charismatic and unaffiliated. The poets are separated in age by some 49 years: the oldest born in 1940, and the youngest in 1989.

Advertisement

The settings range from the Garden of Eden, a South Dakota Benedictine monastery, the 1930s Dust Bowl, the Louisiana bayou, a lake in upstate New York, and beyond. They accept their familial past, their personal challenges, Native to Mennonite, African American, monastic, evangelical.

The poems are funny, sad, angry, joyful; they are human. Some represented poets push fixed forms into new territory, while others work in free verse. Some were born into families of faith; others have found their way to God through alcohol or personal pain.

Denominational and experiential differences evaporate in their shared impassioned refusal to separate their faith from their life and work.

Many of the poets are fascinated with the insufficiency of language, but are driven to persevere, with the need, as Milton put it, "to justify the ways of God to men."

David Middleton (1949) understands his role as a sacred vocation: "For I was also called, ordained, my gift / Not given by a bishop but a voice / That left me with the silence of the page / And language from a common lexicon" ("Ordinations").

"Oh, we have only so many words to think with," ("Staying Power") laments Jeanne Murray Walker (1944).

From left: David Middleton (Courtesy of Nicholls State University); Jeanne Murray Walker (Courtesy of www.jeannemurraywalker.com); Julia Spicher Kasdorf (Philip Ruth)

Belief comes uneasily and at unexpected times to many of these poets. Paul Mariani's (1940) poem, "Quid Pro Quo," narrates a moment of enlightenment several decades after his initial apostasy: giving God the finger in anger over his wife's miscarriage, only to see the son conceived that night be ordained a priest many years later: "How does one bargain / with a God like this, who, quid pro quo, ups / the ante each time He answers one sign with another?"

Often, a poet uses an experience outside traditional settings to depict, with unerring precision, the enormous leap of faith required of a believer. In "The Knowledge of Good and Evil," Julia Spicher Kasdorf (1962) uses a terrifying moment as a child viewing a Snow White movie to demonstrate the preposterous claim of Christianity. Screaming and breathless in the cinema lobby, she is unable to believe the happily-ever-after: "I was a heretic too insulted by the cross / to accept resurrection."

Dana Gioia's (1950) poem "Litany," celebrates life's many paradoxes: "This is a prayer to unbelief."

Christian Wiman's (1966) "Prologue" admits his own struggle with powerful humility: "I need a space for unbelief to breathe. / I need a form for failure, since it is what I have."

From left: Christian Wiman (Courtesy of Yale University); Andrew Hudgins (Wikimedia Commons/Jo McCulty); Tracy K. Smith (Rachel Eliza Griffiths)

Likewise, Ryan Wilson (1982) acknowledges this necessity: "You have no choice / Except to learn humility, / To love this stranger as yourself, / Who won't love you, or ever leave" ("Xenia").

Stunning intimacy with God, those personal "wrestling with angels" moments, form the backbone of several poems. In fact, 10 poems have the word "prayer" in their titles.

In "Praying Drunk," Andrew Hudgins (1951) compares God to Popeye who uses vanishing cream and disappears: "Although you see right through him, he's there." He renders himself as "the poor jerk who wanders out on air / and then looks down," then asks God, "As I fall past, remember me."

There are pleas for forgiveness and words of unusual gratitude, as in Franz Wright's (1953-2015) "One Heart": "Thank You for letting me live for a little as one of the / sane; thank You for letting me know what this is / like."

Mark Jarman (1952) speaks for many in the final stanza of "Questions for Ecclesiastes:"

And God who shall bring

every work into judgment, with every secret thing,

… who could

have shared what he knew with people who needed

urgently to hear it, God kept a secret.

With humor, Marilyn Nelson (1946) skewers hypocrisy in "Incomplete Renunciation." "Please let me have…" the poem begins and lists a realtor's dream house, concluding, "And let it pass / through the eye of a needle."

From left: Mark Jarman (Sarabande Books/Lauren Urquhart); Shane McCrae (AP/Invision/Evan Agostini); Marilyn Nelson (Wikimedia Commons/slowking4)

The title of Shane McCrae's (1975) poem, "Still When I Picture It the Face of God Is a White Man's Face" is indictment enough.

The daughter of an engineer who worked on the Hubble telescope, Tracy K. Smith's (1972) view of the universe is large, searching, searing. In "The Universe as a Primal Scream," she writes:

Whether it is our dead in Old Testament robes,

Or a door opening onto the roiling infinity of space.

Whether it will bend down to greet us like a father,

Or swallow us like a furnace. I'm ready

To meet what refuses to let us keep anything

For long.

Much has been made of declining church attendance in some of the mainstream churches. With that has come a loss in the transmission of shared religious beliefs and, to be frank, the churches' hold on their members. A silver lining may be the new freedom that poets use to explore their doubts and spiritual pain, as well as the joys of belief.

More poems will be written, or discovered because, as Mattis writes in the introduction, "language, as powerful as it is, cannot contain all of reality." One way or the other, humans work to express the particular sliver of reality they've experienced.

These poets have in common that while they have undergone pain and challenges to belief, they remain within or around the fold, rendering their experience with craft, in well-wrought language. Reading these poems, we become their co-conspirators and are therefore in less danger of succumbing to the late William Carlos Williams' warning: "It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there."