Riot police protect Ku Klux Klan members from counter-protesters as they arrive in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 to rally against city proposals to remove or make changes to Confederate monuments in Charlottesville. (CNS/Reuters/Jonathan Ernst)

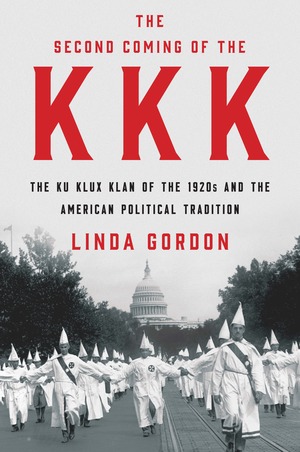

Do Catholics who oppose immigration to the United States today know that they join a long tradition deeply rooted in anti-Catholicism? In its most virulent form, this fear of "aliens" fueled the rise a century ago of a popular and quite powerful Ku Klux Klan. The persistence of that KKK spirit in America, and especially its flowering in recent years, sparked Linda Gordon to re-examine that earlier period. The result, The Second Coming of the KKK, is a compelling exploration of a very troubling movement whose values have taken root in some ironic soil today.

The KKK has had three main manifestations in American history. It started in the wake of the Civil War as a male fraternal order dedicated to a violent reassertion of white supremacy in the American South, and to undermining the federal government's progress toward racial equality for black and white Southerners during Reconstruction. This terrorist version died out as white Southerners successfully re-imposed racial hierarchy through legal segregation.

The KKK next flourished in the early 20th century in reaction to the rush of largely Catholic and Jewish immigrants to America, and also to the release of D.W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation," which extolled the KKK's role in forming a new nation after the Civil War. This KKK lasted only for about a decade, fading quickly after Congress drastically restricted immigration in the early 1920s and KKK leaders were caught up in high-profile sexual and financial scandals.

The KKK's third iteration came in response to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It lasted for a few decades and then too seemed to die. Gordon, two-time winner of the Bancroft Prize, one of the history field's most distinguished prizes, is interested in the second KKK, the 1920s version that targeted Catholics, Jews and African-Americans. Though she focuses on this period, she remains ever mindful of today's social, cultural and political developments and the strong echoes of the early 20th century.

Gordon's history is a cautionary tale. The 1920s KKK was not only a secretive organization whose members terrorized blacks, Catholics and Jews; it was also a public organization that sponsored parades, baseball teams, public barbecues, newspapers, colleges and even a movie production company. It was "mainstream," and worked through the political process to elect and control state governors, U.S. senators, U.S. representatives and a host of local public officials. It even blocked the Democratic Party from nominating Catholic Al Smith for president based largely on religious grounds.

Gordon conveys that the important lesson about the 1920s KKK is not that it provided an organized venue for a small minority to act upon their fear-inspired hate of aliens, but rather that this sentiment resonated powerfully and widely among the broader public. Though it is impossible to reach firm conclusions about who joined or supported the KKK, many historians suggest that the message appealed most to white, Protestant, small-business operators and middle-class professionals who worried that they faced great risk from immigrants, African-Americans, Catholics and Jews. Supporters feared economic unsettledness and displacement, but judged that threat to come from below rather than from those who actually controlled and shaped the economy. The KKK largely supported economic elites and their prerogatives, and instead targeted society's most vulnerable.

KKK membership also provided the opportunity to exercise a wide range of social, economic and cultural ambitions, refine understandings of masculinity, develop a conservative version of female agency and work out versions of "right" living derived from evangelical Protestantism. In Oregon, the KKK successfully advanced a referendum amending the state constitution that required all children to attend public (rather than parochial) schools. Federal courts later nullified the referendum, so the KKK-controlled legislature passed laws dictating which textbooks all public and parochial schools might use, and forbidding teachers from wearing religious garb. Protestant ministers across the nation joined the KKK in droves.

The KKK was able to channel the anxieties and prejudices of a significant segment of the culturally and politically powerful population to support heinous initiatives that demeaned, disenfranchised and endangered many grandparents and great grandparents of those very Catholics who oppose today's immigrants. The return of this spirit, even absent the white robes and hoods, would rightly give us pause. Gordon thinks that spirit has returned; this lends an urgency to her work. She concludes that the "Klannish spirit — fearful, angry, gullible to sensationalist falsehoods, in thrall to demagogic leaders and abusive language, hostile to science and intellectuals, committed to the dream that everyone can be a success in business if they only try — lives on."

Advertisement

That it lives on today among white Catholics is highly ironic. Catholic social teaching embraces immigrants unequivocally, but white American Catholics are more divided.

In a 2015 Public Religion Research Institute survey, 41 percent agreed that the increasing number of immigrants "threatens traditional American customs and values." According to the American National Election Study 2016, 57 percent of American Catholics born before 1942, those closest to Catholic immigrants vilified by the 1920s KKK, voted for Donald Trump — a man who aggressively promoted anti-immigrant messages.

Gordon reminds us that those messages once unjustly harmed European Catholic immigrants and remain pernicious when aimed at those seeking refuge on our shores today.

[Timothy Kelly is department chair and professor of history at St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania.]